A Take Apart Toolkit: What we learn from unmaking

This piece is the first in a series of Field Notes which can be read as a Take Apart Toolkit of sorts, including how to use Take Aparts to engage in deep analysis, to increase accessibility, to explore the complexity of less tangible objects and systems, and more.

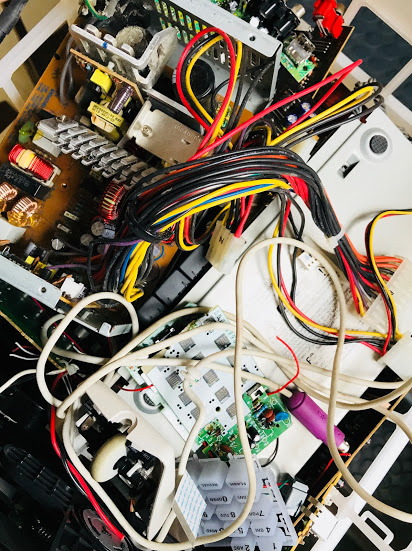

Cracking the case of a computer always inspires a small gasp—an intake of breath that is part fear and part wonder. And it really is beautiful in there.

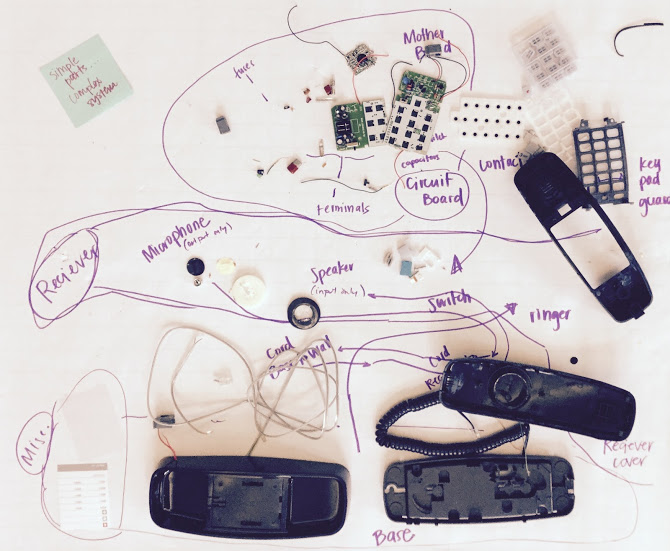

For that matter, so are the guts of a blender or a blow dryer or an FM radio. When I first started using Take Apart practices in the classroom, it was for the simple unwrapping of the incredible miniature landscape inside of the familiar objects that we think we understand most intimately. The view from the inside is a powerful and nearly instantaneous entrypoint into what Agency by Design names a sensitivity to design—that the world around us is designed and made by humans like us, and can be remade, too.

For that matter, so are the guts of a blender or a blow dryer or an FM radio. When I first started using Take Apart practices in the classroom, it was for the simple unwrapping of the incredible miniature landscape inside of the familiar objects that we think we understand most intimately. The view from the inside is a powerful and nearly instantaneous entrypoint into what Agency by Design names a sensitivity to design—that the world around us is designed and made by humans like us, and can be remade, too.

Over time, I came to think of a Take Apart a perfect first dip into maker-centered learning for learners of any age or context because it requires very little prior knowledge. When I’m guiding a group of learners, I like to ask: Look at the object in front of you—do you know its name? Have you ever used it? Most of us can stare down a clock with some level of confidence and firsthand experience. We have a connection to an object we recognize and ready access to what we already know about how it is used, some alternative forms it may have, and even some ideas about how it works. We have memories that may connect it to our home, the Kindergarten teacher who taught us how to tell time, the last clock we touched. A Take Apart has an emotional locomotion that is hard to resist.

A first, essential step is looking closely—slowly observing and reflecting on the whole. One of the key requirements of a Take Apart, and one that I share with learners, is this important permission: You will not be asked to put it back together. You do not need to preserve it. Once the clock is really Taken Apart, it does not go back together, literally or conceptually. It is a plastic rain poncho that can never be stuffed back into its perfect tiny pouch. When we unpack the parts and complications of the clock—when we explore complexity—our understanding of it balloons out dimensionally.

A first, essential step is looking closely—slowly observing and reflecting on the whole. One of the key requirements of a Take Apart, and one that I share with learners, is this important permission: You will not be asked to put it back together. You do not need to preserve it. Once the clock is really Taken Apart, it does not go back together, literally or conceptually. It is a plastic rain poncho that can never be stuffed back into its perfect tiny pouch. When we unpack the parts and complications of the clock—when we explore complexity—our understanding of it balloons out dimensionally.

Permission to break things is a visceral release, and the small shock of cracking the case of a clock marks that crystal moment of transgression. “No going back now,” some learners might say, or “Is this what I’m supposed to do?” They have entered forbidden territory.

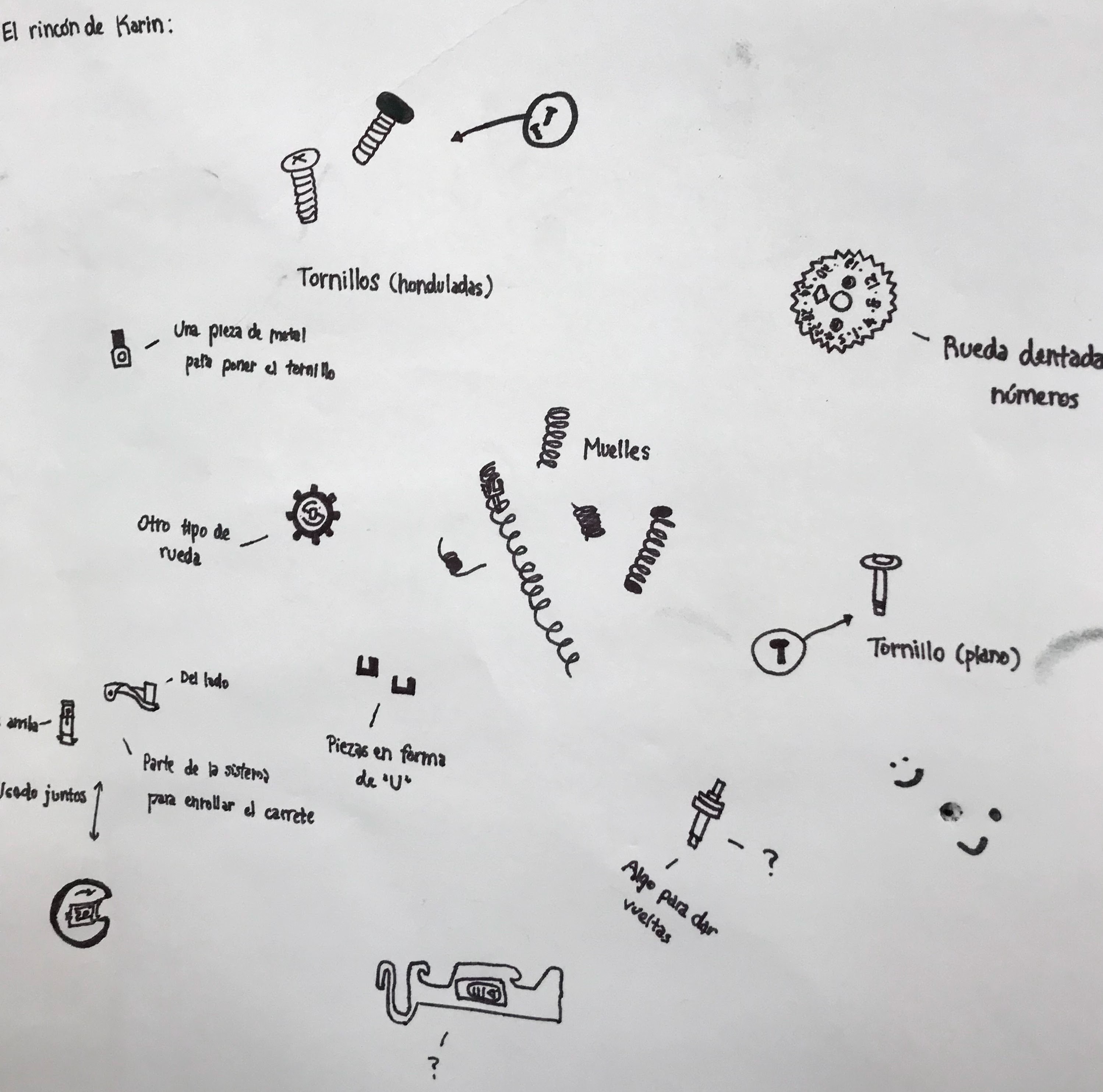

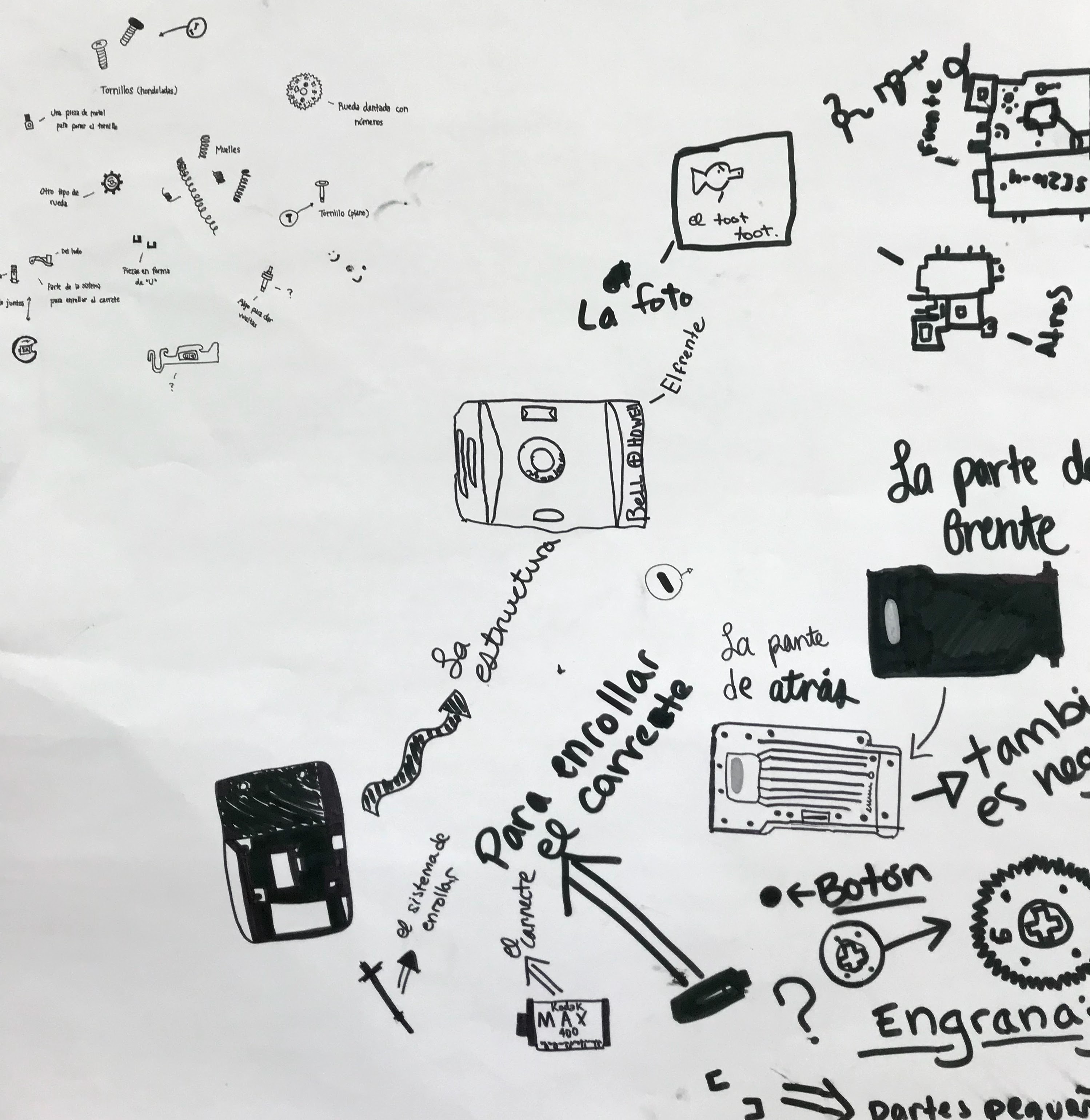

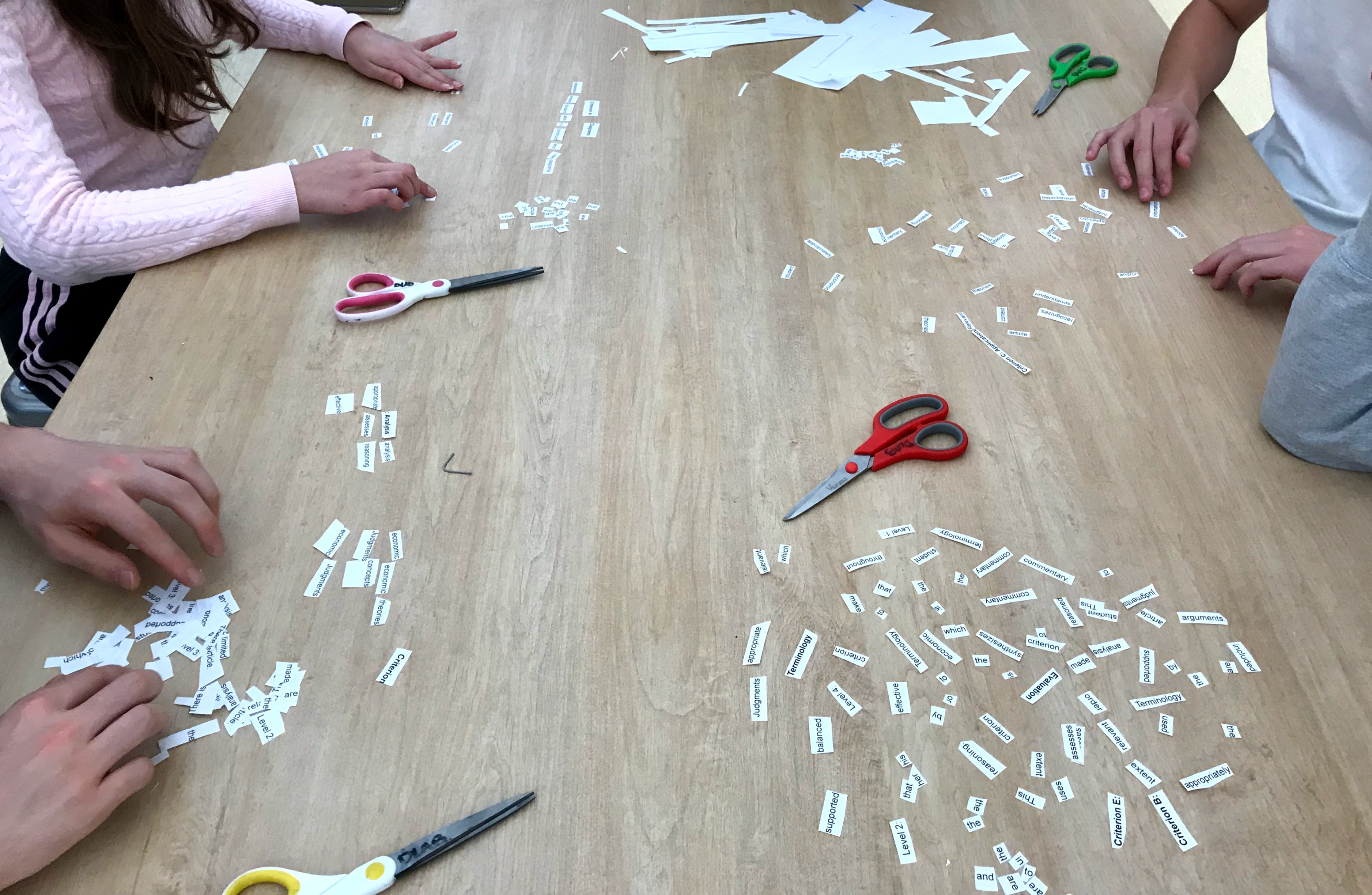

The real processing begins when learners' hands are deep in the guts of the clock and a flurry of questions and inferences rise out of their inherent curiosity. It can get wild in there, and conversations and observations help make order and meaning of what they find. I like to prompt, What do you see? What words or numbers can you find? How are things connected? How does it work to move the hands? As pieces start to come out onto the table, I ask: Sort them in a way that makes sense to you. Is it the way they fit together on the inside? Is it by size or color? What way explains the clock best?

When everything is out, when it is arranged as a representation of our understanding of the clock, it has changed irreversibly. It is broken, for sure, but it is also now physically and conceptually larger than it has ever been. Reflection can make visible how learners’ understandings of the clock and their thinking about it have grown. They can teach what they have learned, or explain a moment of surprise where what they thought they knew about the clock was upended. I often invite my students to consider the following: What was hard about taking it apart, physically or emotionally—and what does that mean? What was hard about explaining its workings? What puzzles remain?

Then finding opportunity becomes a natural next step. Often, learners will ask me if they can keep a piece of this clock. I might ask: Why this piece? What do you want to do with it? What should be thrown away, and what is just too interesting?

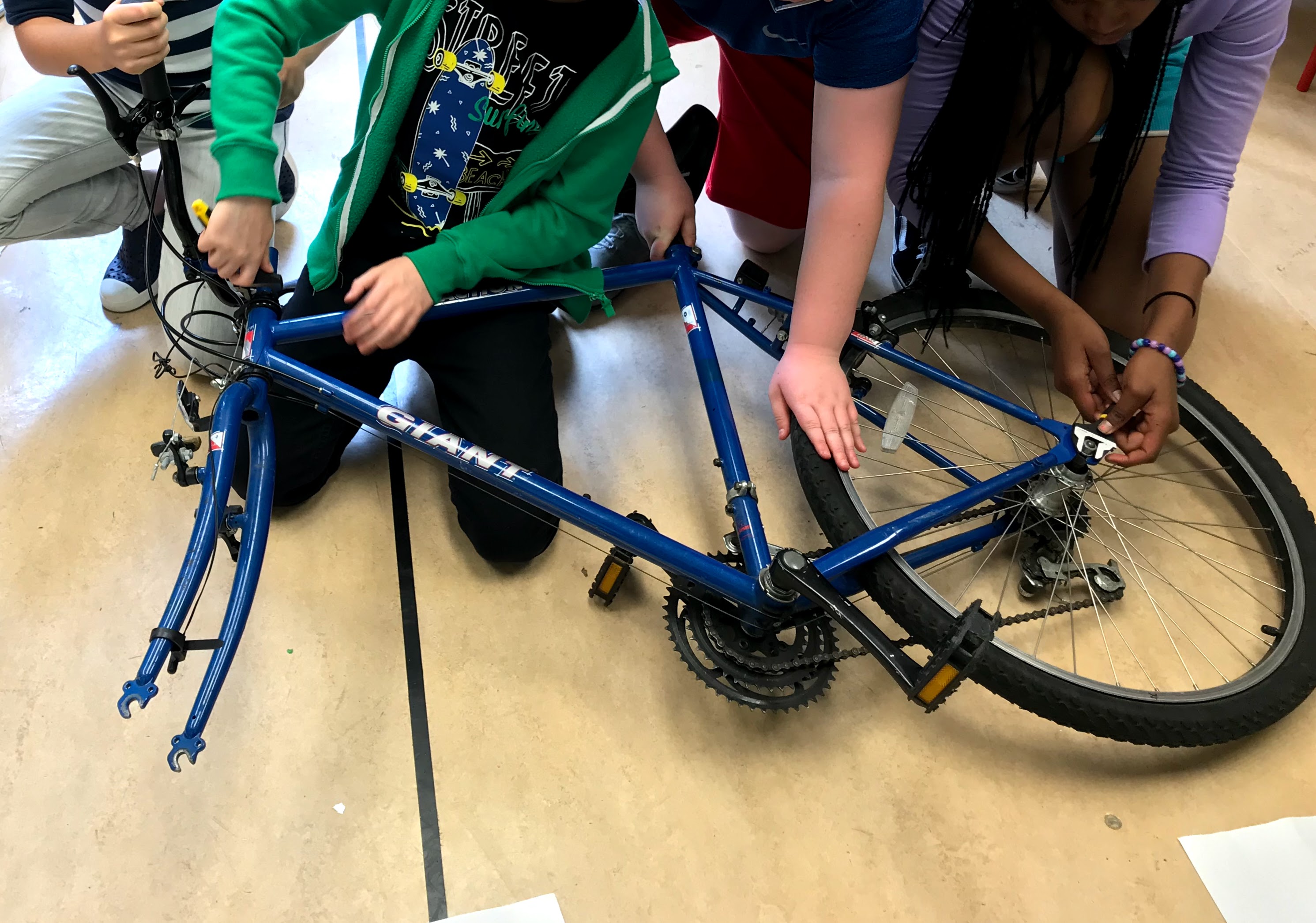

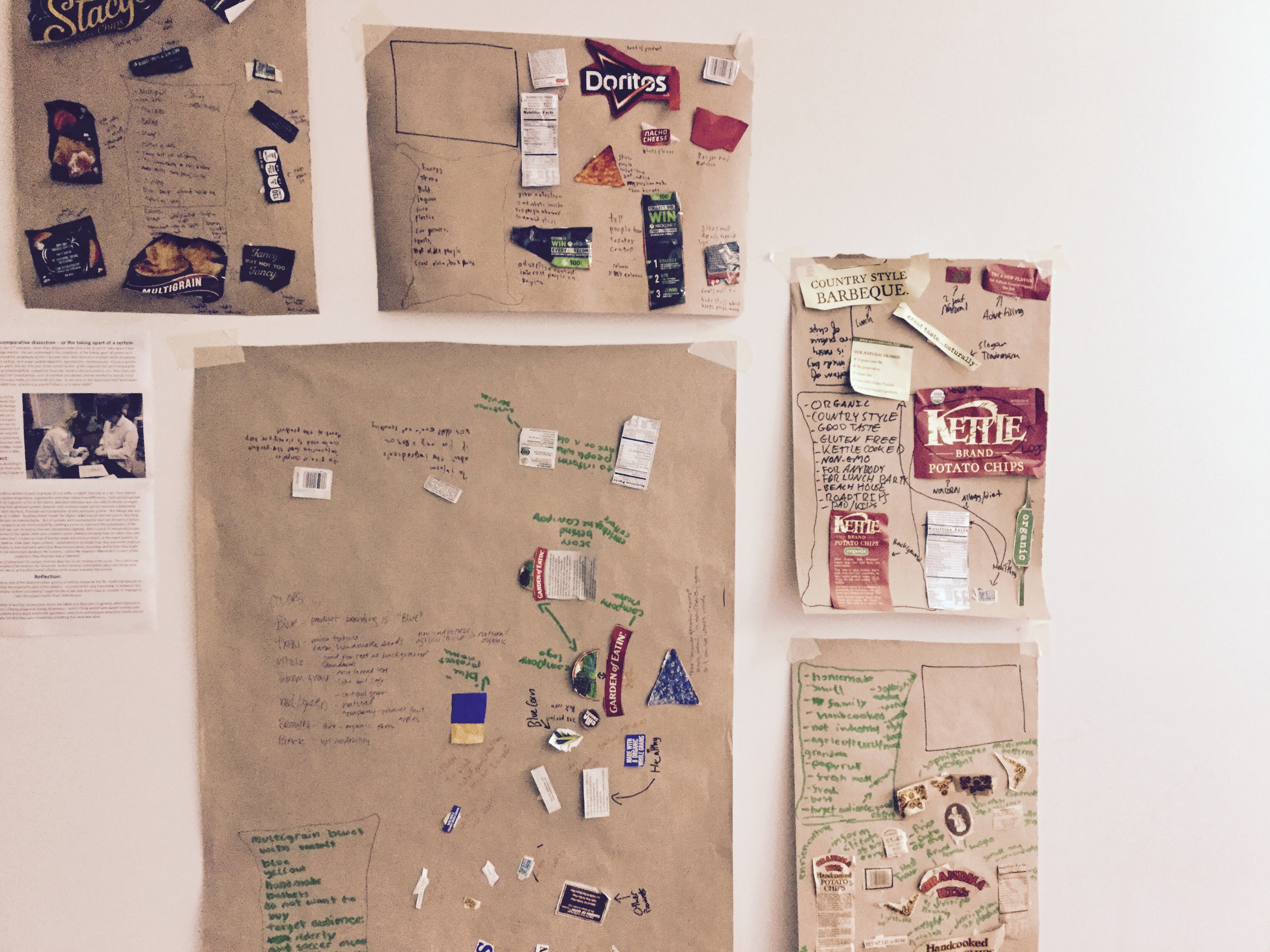

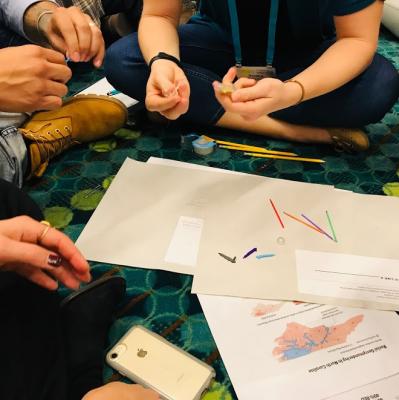

In the past year, the Making Across the Curriculum project at Washington International School has supported our faculty to dig into an exploration of what Take Apart practices might look like in a classroom. The curiosity and enthusiasm of students during a Take Apart is often the most obvious impact, but we are also trying to identify more subtle evidence of student understanding.

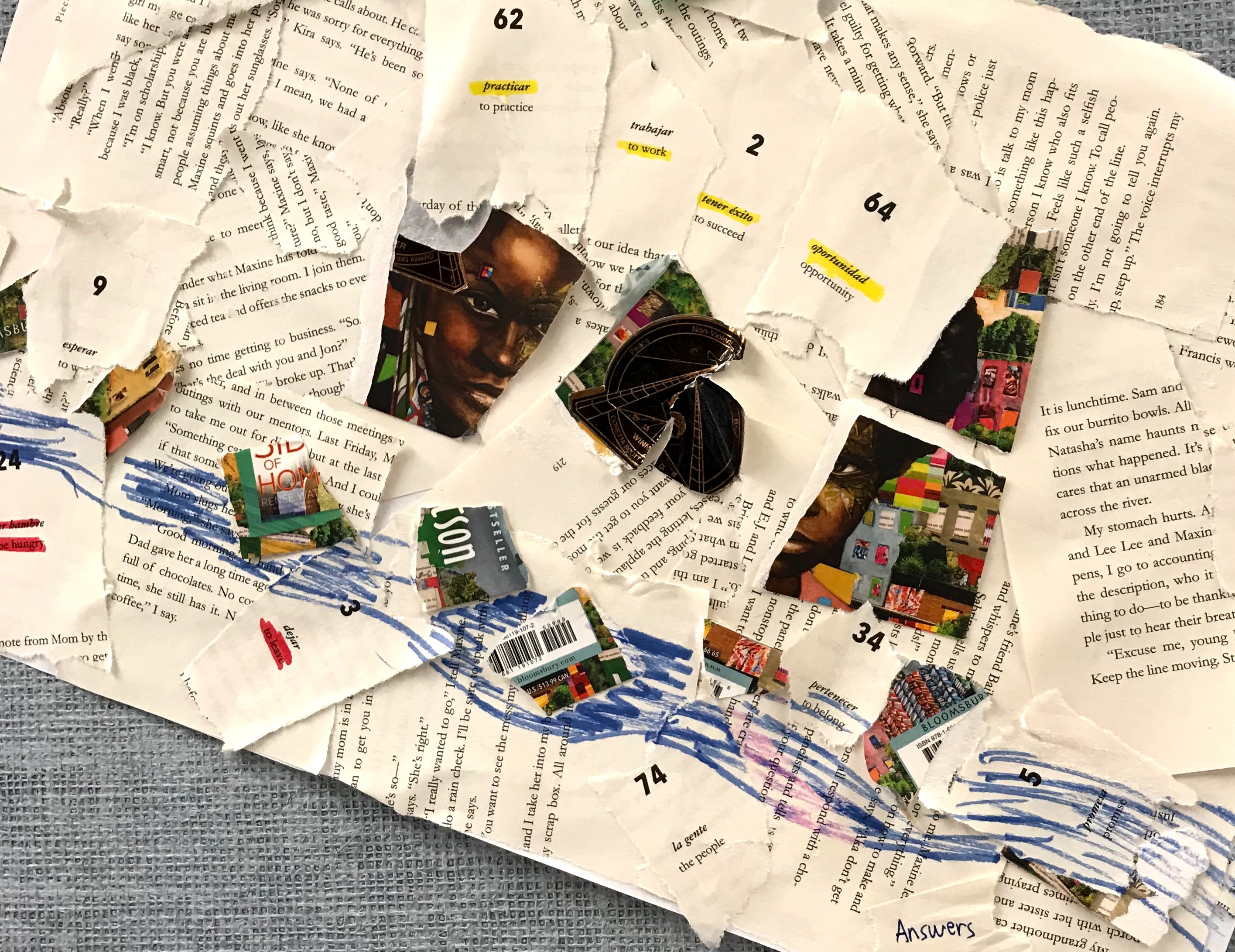

Take a closer look at Take Aparts in three different classrooms at Washington International School:

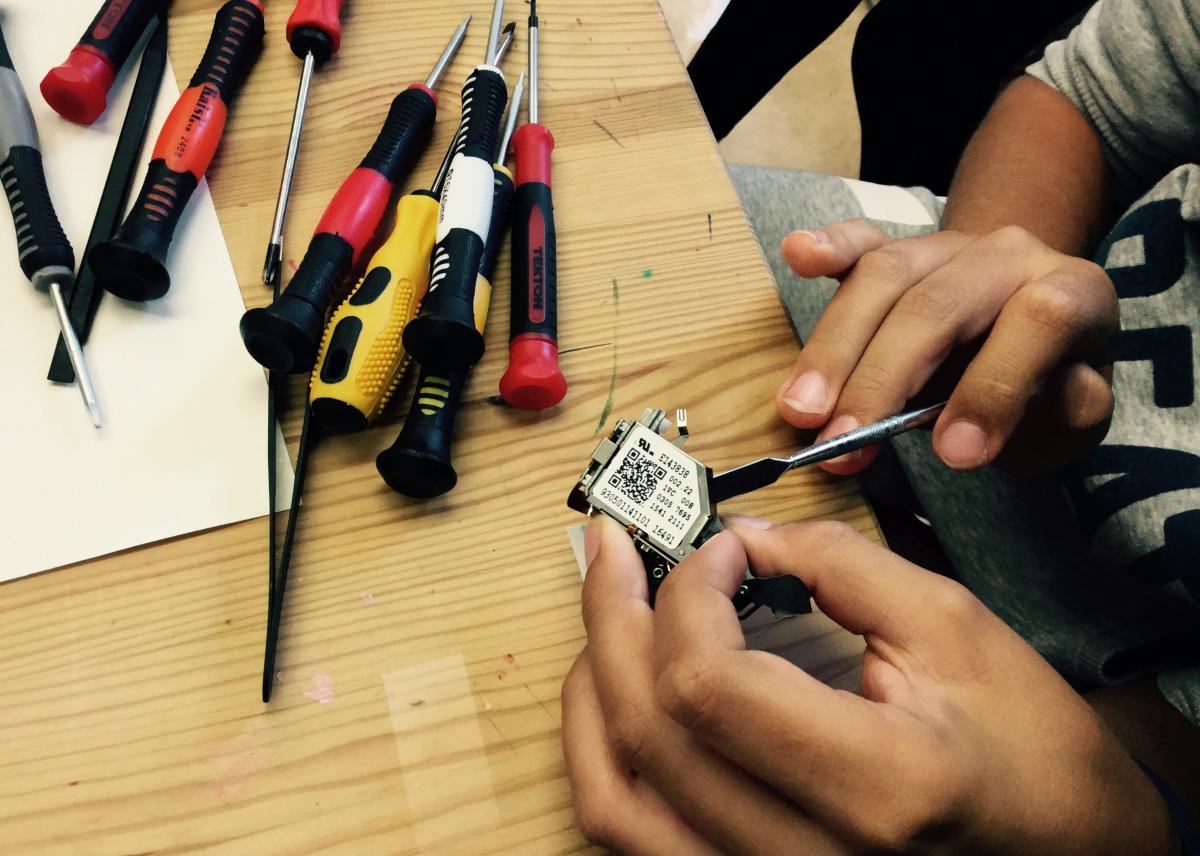

Kerri Redding, the Upper School computer science teacher, invited her class to take apart a computer and relate its parts and their purposes to the computer programs they have been writing. They independently explored the parts, hacking into them to find which ones worked isolated from the overall system. Students deduced the purposes and functions of the parts based on what was familiar from the outside and the internal connections they could spot.

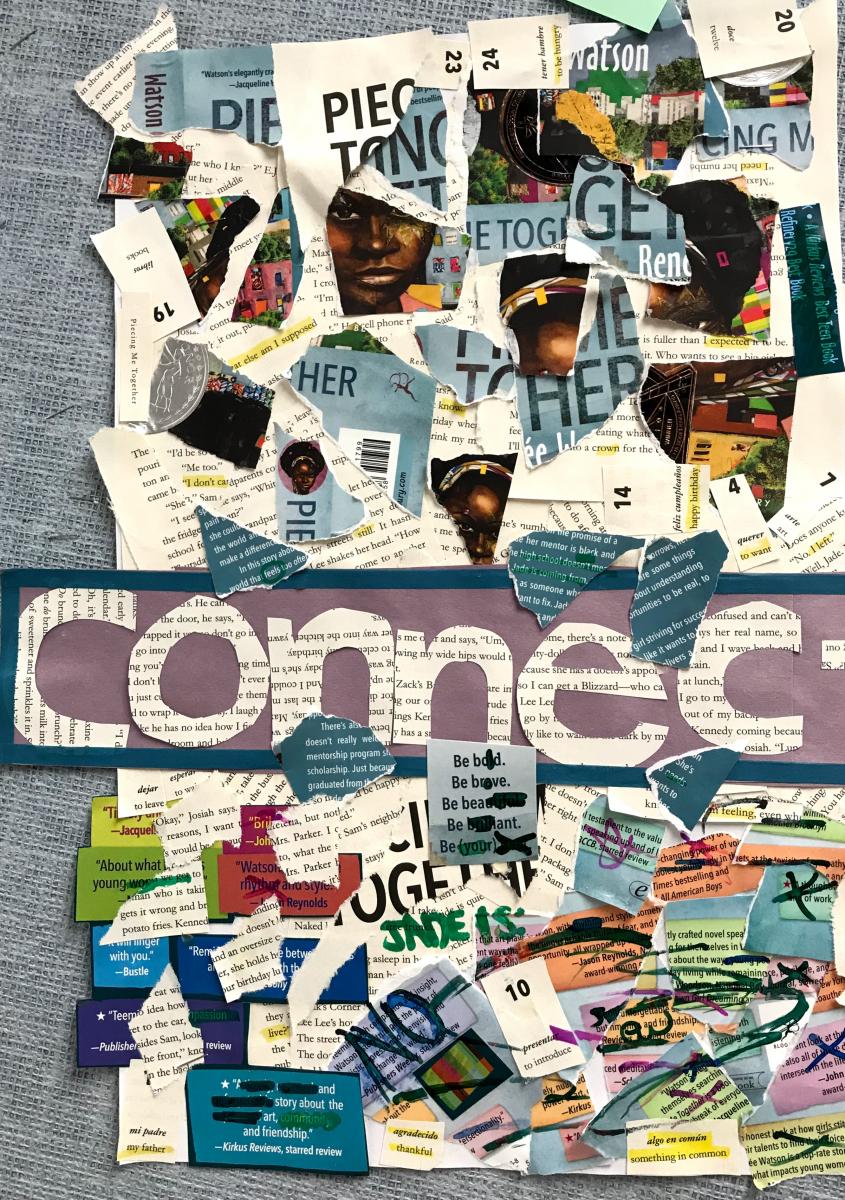

Sonia Chintha, a Middle School English teacher, asked students to take apart their summer reading book Piecing Me Together in order to remix it into a picture of their understanding. They cut up the book and revealed their own emotional connection to the story and the narrator, a young girl who expresses her coming-of-age struggle through collage. Pulling out the structure and themes of the story with the evidence of the text allowed students to ground and relate their ideas.

Mara Wilson’s Middle School Design Technology class took apart water filters and French presses in order to examine the mechanisms of filtration and design their own filtration system for campus gray water. The Take Apart supported their identification of the parts and purposes of filters and anchored their own selection of upcycled found objects for their prototype. It also extended into an important comparison of objects that are designed to be taken apart and how design impacts accessibility.

At the Washington International School, we are taking apart a lot of stuff and finding that it can lead us into a rich vein of inquiry on the structure of knowledge and the way we make meaning. Could these revelations in the world of physical things possibly expose our assumptions about the ideas that feel most familiar? Could they open up the porous border between the external and internal sides of our stuff and ourselves? We will ask these questions and more as we dig deeper into the practice of Take Aparts in upcoming posts.

Explore the slideshow below for a peek into the many ways we're taking things apart.