Esta rutina anima a los estudiantes a considerar las diferentes perspectivas de diversas personas que interactúan dentro de un sistema en particular.

Esta rutina anima a los estudiantes a considerar las diferentes perspectivas de diversas personas que interactúan dentro de un sistema en particular.

Agency by Designer project Director Shari Tishman introduces the concept of “maker empowerment” as a potential outcome of maker learning experiences.

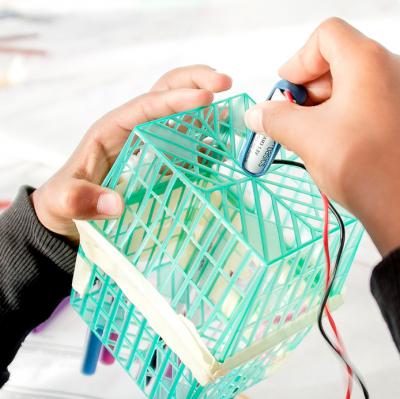

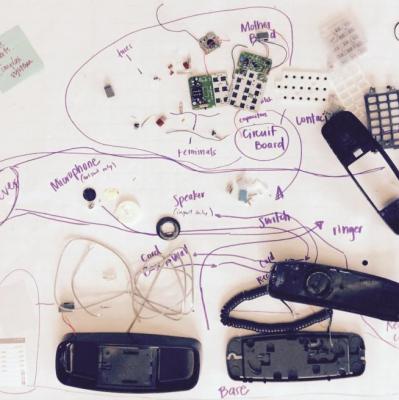

Things Come Apart, by Todd McLellan provided some inspiration for educators from Park Day School to explore the complexities of everyday objects with their second grade learners. In this picture of practice essay educator Jeanine Harmon shares the project.

Featured photo by Jaime Chao Mignano

PROTOCOLO PARA ANALIZAR DE FORMA CRÍTICA UN CONTENIDO, CONSIDERANDO DIFERENTES PERSPECTIVAS Y REPRESENTACIÓN, PARA DESPUÉS REDISEÑAR O REIMAGINAR ESE CONTENIDO DESDE UNA PERSPECTIVA PROPIA.

This thinking routine helps learners slow down and look closely at a system. In doing so, young people are able to situate objects within systems and recognize the various people who participate—directly or indirectly—within a particular system.

This routine encourages divergent thinking by prompting students to think of new possibilities for an object or system. It can also encourage convergent thinking by giving students a basis from which to narrow down their ideas so they can redesign or hack an object or a system. Ultimately, this thinking routine is about finding opportunity and pursuing new ideas.

Agency by Design Principal Investigator Shari Tishman takes a dispositional approach to redefining “maker empowerment.”

这个思考模式鼓励学生在一个特定的系统里思考不同人物的观点。其目标是帮助学生理解系统里的不同角色,他们会用什么形式去表达感受以及对系统里其他人物和事物的关心。

Just as the broader Agency by Design framework for maker-centered learning encourages people to be active creators of the designed world, the Hacker Helper Tool invites educators to view the breadth of educator resources associated with the Agency by Design framework as malleable. This tool provides prompts to support educators as they “hack” existing Agency by Design tools, practices, and thinking routines to work better for their learners.