这个思考模式通过让学生慢慢、细心地观察物件和系统中的细节,鼓励他们不止观察物件的表面特征,更重要的是了解其内部运作。

这个思考模式通过让学生慢慢、细心地观察物件和系统中的细节,鼓励他们不止观察物件的表面特征,更重要的是了解其内部运作。

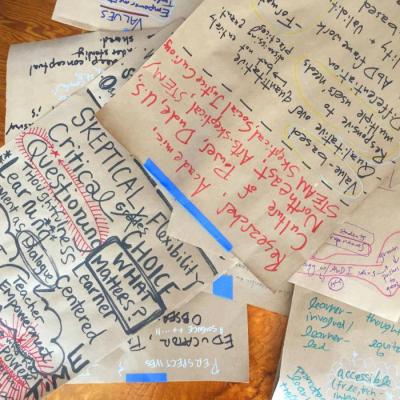

Synthesizing recent conversations between AbD and the Oakland Leadership Team, AbD researcher Andrea Sachdeva proposes a values-based stance on documentation and assessment in maker-centered learning.

Maker-Centered Learning And The Development Of Self: Preliminary Findings Of The Agency By Design Project

A White Paper Presented By Agency by Design

Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School Of Education

This White Paper, from January 2015, presents an overview of our developing work, and concludes by presenting the “big take away” from our research and by making suggestions for policymakers, educators, and other stakeholders. Along the way, we identify what we consider to be the most salient benefits of maker-centered learning for young people and, introduce some of the key concepts and resources that have emerged from our work, including the concept of maker empowerment, the importance of developing a sensitivity to design, and the three pathways that lead to these desired outcomes.

Agency by Design researcher Jen Ryan explores some of the central ideas from the framework at TEDxDirigo Generate.

The Inquiry Cycle is a tool to support teacher and student learning—and to make that learning visible—all the while exploring the capacities associated with the Agency by Design framework for maker-centered learning.

这个思考模式鼓励学生能够慢下来,仔细观察其中一个系统。通过这样帮助学生更好地认识具体系统里无论是直接或间接相关的人物,学生也会注意到系统里任何一点变化,也许都会有意无意地影响到系统的其它方面。

High School technology students in Darlease Monteiro’s class use Parts, Purposes, Complexities to analyze website apps prior to designing their own.

Oakland Learning Community member Ilya Pratt describes her experiences working with the concept of “Maker Empowerment” at a recent Agency by Design workshop in Oakland, CA.