Designing and Making with English Language Learners

Thi Bui teaches art and multimedia at Oakland International High School, a public high school for immigrants students’ where command of the English language is one of the last things to be taken for granted.

I teach art and multimedia at Oakland International High School, a public high school for immigrants students’ where command of the English language is one of the last things to be taken for granted. Discussions are often clumsy or stiff because improvised speech in English is very difficult for beginners. As a result, sometimes it’s difficult for me to know what my students are thinking. Through the Agency by Design research initiative, I have the opportunity to explore, with support, this question: How might design thinking, maker culture, and Project Zero ideas help create an enriching and empowering learning experience for English Language Learners (ELLS)?

To seek answers, last June I decided to get my hands dirty.

My planning partner and I created a design course for Post Session, a 3-week period at the end of the year reserved for experiential art and physical education. classes. Twenty-five to thirty students, mixed grades, two teachers, all day. Here’s what happened…

Using the Parts-Purposes-Complexities thinking routine (from Project Zero’s Artful Thinking framework), students looked closely at the school for areas and systems that they wanted to improve. After narrowing down a very BIG brainstorm into a few priorities by discussion and vote, students worked in groups to rapidly prototype a system or area redesign. Then they presented their ideas to each other and another class.

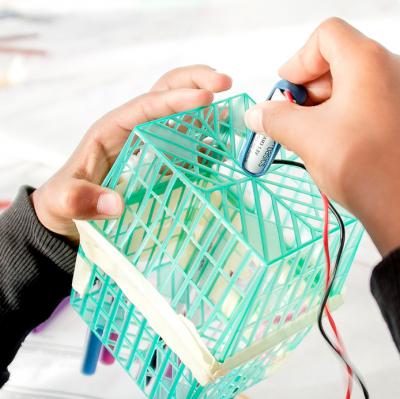

During the prototyping and presentation phase I noticed two things about ELLs. The level of engagement in the redesign process is strongly affected by (1) the student’s comfort speaking in English and (2) by his/her comfort working with materials. Those with more English were able to involve their team mates in brainstorming and the exchange of ideas through words. They could also help negotiate differences of opinion and felt more comfortable presenting to others. Those with the ability to manipulate materials to express their ideas could often transcend language barriers entirely. It was a joy to see them smiling and getting through to others. Those with both English and material fluency had a blast! Unfortunately, I think students who were uncomfortable with both English and materials had a difficult time with this part of the design process, and began to disengage.

This is where I made a quick decision to stray from the design thinking model I was using, which would have had us testing and revising student prototypes through a largely discussion-based method of exchange. I felt, at that moment for my beginning ELLs, that there was simply too much talking in the design thinking approach. I wanted to address the question that many students asked in our first phase of design: I wonder if the school will really change?

What I did to shorten the space between designing and making borrowed ideas from maker culture and design-build practice, both strong trends in the Bay Area.

1. Bring in an expert

In maker culture there is often a resident expert or something to replace that expertise (like a DIY kit), a transfer of knowledge through going through steps thought through by someone else, and a hope that you will move beyond the kit into something more your own.

My husband, a carpenter and artist, looked at the students’ prototypes for a corner garden within the school and responded with some ideas about how to execute their idea to build a set of benches with an economy of materials that would also be durable. He and I bought the materials and did some of the heavy cutting, and students (with my guidance) built the benches.

2. Involve students in decision-making, and increase their awareness of those opportunities

There were countless moments in building the benches and redesigning the rest of the garden when we needed to make decisions about materials, how to join two materials, cost, tools, size, placement, etc. Students learned that putting up a trellis doesn’t have to mean going to Home Depot and choosing one off the shelf. They could build one with materials that made sense for the space and decide the dimensions based on the space and their intent. Similarly, designing a pathway and then actually having to make it level heightened their sensitivity to designed systems they had taken for granted before, including—literally—the ground they walked on.

My take-away: Design happens in the making of things, not just in the planning. And for the ELLs I work with, many of whom didn’t know the words “hammer,” “drill,” or “tape measure”—much less words like “ideate” or “prototype”—it was far more satisfying to communicate and work together in the actual physical space of the area we were trying to redesign.

Was agency a by-product of this design-build experience? I think yes. So was community. Could thinking routines, protocols and more language scaffolds help develop students’ capacity for discussion? I think yes. Could working with actual building materials earlier be a valuable part of the design thinking process? Possibly. And I can’t wait to try all this again.

* * * * *

Thi Bui, a founding teacher at Oakland International High School, was born in Vietnam and came to the U.S. as a refugee when she was a child. She received her BA in art and legal studies from University of California Berkeley, an MFA from Bard College, and an MA in Art Education from New York University. Thi taught in New York City schools before returning to the Bay Area and joining the staff of Oakland International High School. Thi has also worked as an educational consultant with the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum in New York and as a curriculum writer for PBS/ Art:21 Education Council. In 2010, she was named the winner of the National Plank Fellowship Award by Fund For Teachers. In 2012, she received the third place national Unsung Heroes Award from ING for her Immigrant Voices documentary project. She is currently working on a graphic novel about the Vietnam War and her family’s immigration. In addition, Thi is a School Liaison working with the Oakland Learning Community in conjunction with Project Zero’s Agency by Design research initiative.