Maker – Person, Identity, or Culture?

Agency by Design project manager Jen Ryan examines the use of the word maker and offers an alternative reframing for an emerging field.

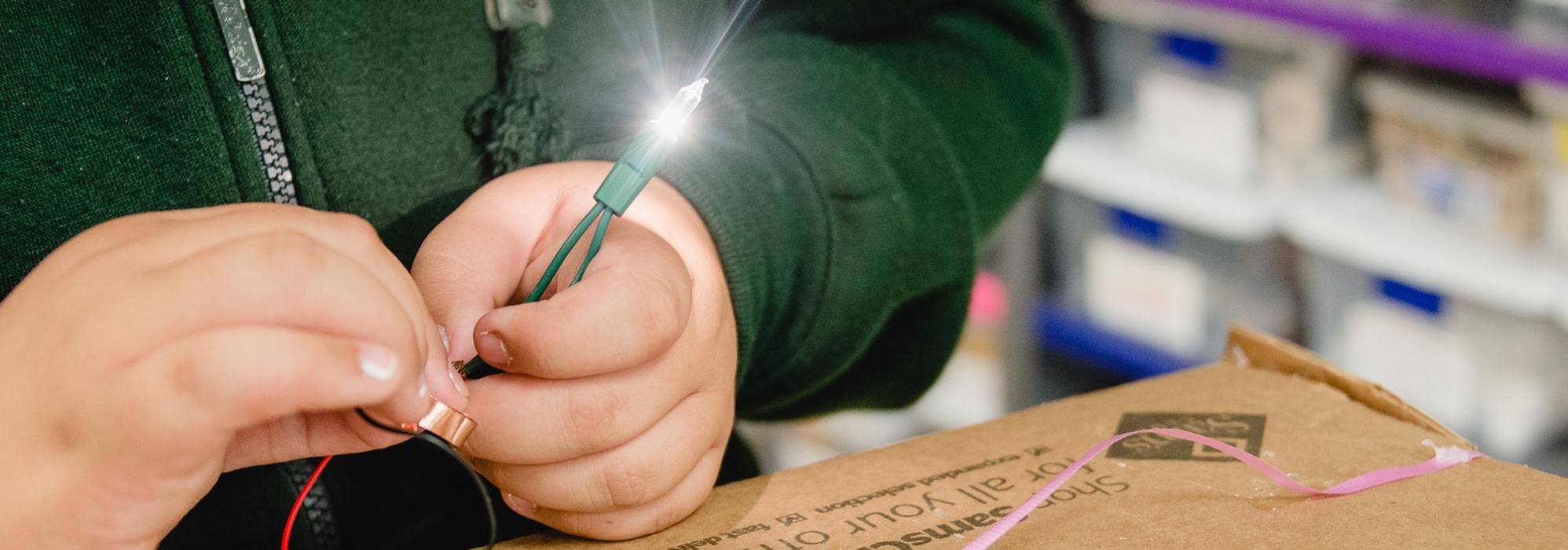

To most, the word maker conjures up images of people working with their hands—designing, building, and crafting. Seen in this light, maker is an identity, a noun, perhaps even a profession. A maker might be someone who bakes bread or someone who quenches steel; it might be someone who builds chairs or someone who paints portraits. Ultimately, as Debbie Chachra points out in her article I am Not a Maker, a maker is someone who makes things.

Granted, maker culture and the maker movement are aptly described as being made up of makers. But a quick pass across the popular press and media shows a prevalence of a certain type of maker: DIYers with expertise in robotics, technology, and electronics, working with innovative tools and technologies such as 3D printers, micro-controllers, computer numerical controller (CNC) tools, and open-source platforms. The outcomes and programs of the movement are commonly billed as being about entrepreneurialism, innovation, and participating in a newly-defined, democratic, producer-based manufacturing system. And, as Leah Buckley has criticized, the narrowing of maker types isn’t just about domain and product: a limited representation of the people being identified as makers is prevalent as well.

Highlighting the ‘er’ version of make certainly surfaces issues of equity and individual identity. But a shift in semantics around the use of the term maker are also presenting tensions around collective identity. Trends in popular culture have secured a new way of thinking about the term: maker as adjective. Maker culture, maker space, maker classroom, maker movement. While being a maker continues to suggest someone who makes things, participating in a movement implies (is predicated on?) belonging and identity. To be a part of a community means adhering to its practices, norms, and responsibilities: Can I participate in this movement? Do I—or does my work—qualify me to be a part of this community?

Unfortunately, along with a sense of belonging comes the implicit corollary—not belonging. And this is where the label “maker movement” just might do itself a disservice. By putting boundaries around makers in the shift to maker-as-cultural-identity, we run the risk of excluding those who might ordinarily consider themselves makers. Those bread bakers and chair builders might identify with others who make things, but not necessarily with the maker culture as it is portrayed and promoted in social media and the press.

The mashup of maker and movement surfaces challenges. Yet much of the tension stems from semantics. Perhaps the “making movement” would have been a better name, capturing what people do rather than who they are. Yet there is something unique about the kinds of activities and culture in which the maker community engages. As we’ve learned from our own research and the field (see the work of David Gauntlett and David Lang, for example), the community is important. The norms are important. So how do we at once make the maker movement and maker culture more inclusive while recognizing that the work happening in makerspaces and maker classrooms does have a distinctive ethos?

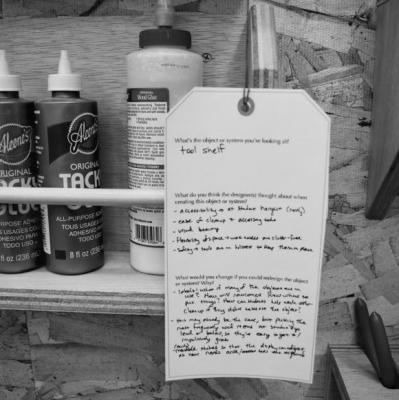

The AbD team is playing with a two-pronged way to address this issue: 1) reframing how we describe the kinds of activities we’re researching as maker-centered with a focus on the learning goals (i.e., maker-centered learning), and 2) considering a symptomatic approach to defining what the maker in this context means. Each of these moves allows us to stretch the boundaries of maker: maker-centered is more nuanced than just making, and a symptomatic approach to defining the term means that we can consider a constellation of characteristics that indicates maker-centered experiences but does not require their presence conclusively. In other words, to “qualify” as maker-centered it would not be necessary to embody all of the characteristics; rather, exhibiting a majority of the characteristics in any configuration would suffice.

While we are still analyzing our data and don’t yet have an index of the symptoms of maker-centered learning to share, some patterns have emerged. Certain characteristics exemplify the components typical of maker-centered learning experiences and seem to describe a particular:

- Culture: (e.g., disruptive, curious, forward-looking, experimental)

- Community (e.g., collaborative, distributed, creative)

- Process (e.g., iterative, interdisciplinary, flexible)

- Environment (e.g., open, accessible, tool/media rich)

In some sense, one might argue that it doesn’t really matter how we (researchers, educators, students, the press) define maker. It’s all semantics. But as we veer closer and closer to considering maker as a field, discipline, domain, or profession— with educational implications and responses such as assessment, standards, curriculum design, and teacher training—precision of language and terminology are important, and boundaries do matter.

Boundaries have been drawn around domains of practice and, in the process, have unwittingly set up a false dichotomy between those who participate in the maker movement and those who don’t. Perhaps re-focusing on the what and how of maker-centered learning, rather than the who, can help push us all towards a more inclusive, less siloed, and stronger community of makers.

We wonder if our readers—those of you who are artists, makers, working in or thinking about the field of maker-centered learning—have thoughts about maker as person, identity, or movement. How do you define maker? What boundaries, if any, would you place around maker-centered learning?